Way back in January I had the incredible privilege of visiting a number of farmers and seed company folks in northern Italy, and specifically looking at radicchio and other chicory growing there. I was going to do a workshop for local market farmers here in the Portland area in early April on what I learned there but that didn’t exactly work out due to the current pandemic. I’ve decided to move the workshop to mid-May and online. Check out the flyer here if you’re interested and want to sign up. It’s free thanks to a generous donation from my friend Eric Pond at Greenleaf Farm Management and as most of these crops are best seeded starting in June and July we should still be early enough with the information to make it useful this year!

2019 Numbers

I’ve always been public with the numbers for my farm ventures. You can go back to my report from last year with this link here , and that post links to years prior. I’ve been glad to see more folks, especially folks who are teaching and consulting starting to be more public with numbers, although the most common number I see is total gross income, or gross per something – acres, or square feet, or some other measure.

I’ve always understood gross income to be a poor metric for understanding the success of a farm when it’s not given in relation to expenses and other factors. For the past few years I’ve been gaining more and more insight into measures of health and success for businesses in general, and farms in particular. My partner went and got her MBA after many years of farming, specifically to work on this topic, and I’ve probably been the biggest beneficiary of her degree at this point – absorbing a lot of what she learned through many, many conversations on the topic, and even co-writing the chapter “Manage It” in the new book, “Whole Farm Management ” from Storey Publishing, which was put together by the Oregon State University Center for Small Farms and Community Food Systems .

I’m still convinced that the best all-around metric for comparing how my farm did from year to year – and for that matter, comparing it to other farms of any scale – is to use the dollars per hour generated after non-labor expenses, or maybe it should be called the net dollars per labor hour.

I calculate this number using three numbers: total gross income, total labor hours, total non-labor expenses.

Total gross income is the easiest and clearest number for me to calculate. It’s simply all of the cash income the farm generates during the year. The only thing that’s not included that might be significant in some way are non-cash benefits. These would be things like the extra food produced that all of us who work on the farm take home each week, or little thank yous like the chocolate bars one of our CSA members brings us regularly, or the flower bouquets another makes us.

Total labor hours is also relatively easy as all of the employees on the farm are paid hourly and I track my own labor hours as if I was paid hourly. In some sense I actually do pay myself at an hourly rate, although as the owner I also take home any additional profits. For farmers who are resistant to tracking their hours, or just don’t do it, you’d have to take a really good guess and based on tracking my own hours I’d guess that many folks are vastly overestimating the number of hours they actually work on the farm (I try to use labor laws as my guide for what an hour of my work is, even though as a business owner I’m not bound by employee labor law and I can work as many hours as I like, whenever I like). For the total hours I’m adding up everything that everyone worked with direct benefit to the farm regardless of their skill level or payrate.

Total non-labor expenses are the trickiest of the three numbers to be consistent with. I immediately take out any payroll expenses as those are labor expenses. For large equipment or infrastructure purchases I’ll try to reasonably estimate their useful life and do a straight-line depreciation (there are more accurate ways to do this, but I think straight-line is close enough considering how many of these I have). Some expenses are a little questionable as to whether they are really necessary, or maybe as to whether they should be in the labor category. An expense that I question including sometimes is a tool or piece of infrastructure that isn’t one that is absolutely necessary for production, but that simply makes our work nicer in some ways. For example if I were to buy a sound system for the barn so that folks could enjoy music while they work I’m not sure I’d include it (not a purchase that I’ve made, but a good example I think). I also bought a nice seeder we didn’t need but that I wanted to try last year. It was relatively expensive and I wasn’t sure I should include it, another example. Any expenses for employee benefits, like end of the year celebration dinners, or even buying the crew their own personal harvest tools are always a bit fuzzy for me as well – are they labor expenses or non-labor expenses? Generally these are small enough that I don’t worry too much about which category I put them in as they won’t ultimately make a big difference in the final number.

This year the total gross of the farm was $41,226

The total labor hours were 2088

The total non-labor expenses were $7,064

This brings the net dollars per labor hour to about $16.36

This is lower than in 2019 but it’s actually not as much lower as I feared it might be. I’ve also talked to a number of long time, very successful farmers over the years that have told me that over decades they see a lot of ups and downs from year to year. Here are the factors I think contributed to the lower number this year: weather, a completely new crew, and pest pressure.

The weather wasn’t actually too bad this season. It was a colder start to the year and a rather abrupt end to summer, so those worked against us in some ways. Slower growth in the spring and early summer meant the crops were less competitive with weeds which increased our labor needs there and might have increased our harvest labor a bit in some of the roots – smaller roots take longer to harvest. The abrupt end to summer had mixed results for costs. In some ways it is actually a short-term benefit in our situation. CSA members pay up front and absorb some of the shortfalls when crops yield less than we hope or fail all together – there can be a labor savings when we don’t harvest. In other ways it makes us have to scrape a little harder to give full shares every week and that increases the labor costs for what we are harvesting. As an example, we were uncharacteristically short on kale and collards in the fall and really had to spend a lot of time sorting through damaged leaves to get decent bunches – that cost us.

That sorting through the kale might have been partly due to weather but it was actually mostly due to pest pressure. Pests also cost us a lot of extra labor dealing with holes in drip lines this year – it was the worst year for chewing on irrigation lines I’ve ever seen by far! Pests also took out our initial planting of corn and winter squash which had cascading effects, resulting in a lot of extra labor weeding and very low yields without much harvest labor savings.

Last year we had a couple of folks on the crew who were new to the farm, but there were three of us in the core crew that had at least three seasons on the farm, and two of the “new” crew members had worked with us a little in the past. It turns out it makes a big difference when the crew is experienced and knows what to expect. It takes a lot less time to explain what tasks need to be done, and it takes the crew a lot less time to make transitions from one task to another. It’s also a big difference if only one or two people are new and they have multiple other folks to take cues from. In 2019 I was the only one who knew any of Cully Neighborhood Farm’s specific systems. The crew this year was a great group of folks (and I hope they come back to work with me again), but even though they all had some farm experience in other places, none had worked on this farm and so things just took longer. You can see that reflected in the total labor hour numbers between 2018 and 2019.

Even with the drop in net-dollars per hour generated I’m pretty happy with what we were able to do in 2019. I’m especially happy that the number comes in above $15/hour (the target for minimum wage in Portland over the next few years), although probably not enough above $15/hour to cover the “loaded” hourly rate. The loaded rate has to cover the business’s payroll taxes as well as the hourly rate. In addition, it doesn’t leave much room for anyone to make much over minimum wage.

Championing Chicory

A couple of months ago I created an Indiegogo campaign for a project that Lane Selman, Shawn Linehan and I are doing. The crowd funding campaign through Indiegogo was my first direct insight into that platform and it was an interesting experiment in some ways – definitely successful in a lot of ways, but also possibly the wrong platform for the amount of time we had to commit to promoting the campaign. Now that the campaign has expired we’re still getting inquiries for how people can help support our work so I’m reposting most of the information from the campaign below. Donations can still be made through the PayPal link at the bottom of my pages here, with the same “thank yous” we gave on the Indiegogo campaign. Or, if you prefer to mail a check just send me an email and I’ll get you an invoice with the mailing address.

Please help support a small expedition of Pacific Northwest farmers and farm educators headed to northern Italy in January to learn more about both production methods and culinary uses for this quintessentially Italian crop, and to bring back that information for growers, cooks and eaters.

The Expedition is being organized and led by Italian farmer Myrtha Zierock of Foradori Winery and Farm in Mezzolombardo, Italy, and Lane Selman of the Culinary Breeding Network in Portland, Oregon. We will visit production farms, seed companies and radicchio breeders throughout the Veneto region for five days. The expedition will culminate in a public event and radicchio celebration called Giàz (meaning ‘ice’ in the Trentino dialect) at Foradori.

Outcomes will include articles, photographs, video and presentations for the public, all focused on increasing understanding of radicchio production and culinary usage. Information will be shared at the third annual Sagra di Radicchio event in Seattle, WA in 2020 which we hope to expand into a multi-day conference this coming year.

Sponsorship will help cover travel expenses and the development of educational materials for the primary documentarians on the trip: Lane Selman of The Culinary Breeding Network, Josh Volk of Slow Hand Farm Consulting, and Shawn Linehan of Shawn Linehan Photography.

Background – Radicchio is a cool season vegetable that originated and is still widely grown in the Veneto region of northeastern Italy, a climate of annual mean temperatures, and latitude very similar to those of the Pacific Northwest. It is a promising winter crop as it overwinters in the field and holds well in storage, providing a locally grown alternative to lettuce shipped from warmer regions during the colder months. Numerous farmers in Oregon and Washington are interested in growing radicchio, but have production questions on variety selection, seeding and transplanting timing, cultivation, harvest, forcing techniques and storage. Little of this detailed information is available in the US and the best way to acquire details by directly visiting the farmers growing these crops in Italy. An initial visit to radicchio seed breeders in 2014 was an invaluable introduction to many basics practices that were not commonly known in the US and this second trip will build on that information by visiting more growers in the region and documenting their practices.

According to growers in the northwest and northeastern US, radicchio demand has increased exponentially over the past decade and recent years. Local Roots Farm in Duvall, WA has reported a 900% increase over the last decade and a doubling in sales in the past year alone. Radicchio sales currently account for 12% of their total annual sales to restaurants, and they expect that growth to continue. Hayshaker Farm in Walla Walla, WA have seen sales increase 250% from 2017 to 2018 and they also see demand continuing to grow.

On the East coast, Kitchen Garden Farm in western Massachusetts has doubled sales in the last year with $30,000 in radicchio sales for 2018 making the crop a significant part of the farm income, not just something novel and fun. Since 2017, Kitchen Garden Farm has been primarily selling vegetables through distributors, and directly to stores and restaurants, in NYC, Boston, and Providence. More than 60% of their 2018 radicchio was sold to NYC through Natoora and Myers Produce.

In the US, the California-grown, round, red Chioggia type is the most commonly found radicchio on grocery store shelves. Pacific Northwest growers are producing a much wider variety of radicchio types including Treviso Precoce, Treviso Tardivo, Castelfranco, Lusia, Verona, Rose, Puntarelle, Grumolo and more. Each has a unique appearance, flavor, texture and culinary purpose. And each have their own set of growing methods which we hope to learn more about during the “Radicchio Expedition in Veneto, Italy 2020”.

LANE SELMAN AND THE CULINARY BREEDING NETWORK

The Culinary Breeding Network is an initiative created by Lane Selman with a mission to break down the walls between breeders and eaters to improve agricultural and culinary quality. Read more about the Network at www.culinarybreedingnetwork.com.

SHAWN LINEHAN

Shawn Linehan has been photographing small-scale farmers and seed breeders since 2008 and has photographed at all CBN’s Variety Showcases. Traveling twice to Japan with Stacey Givens of The Side Yard Farm & Kitchen sparked a desire to photograph more farming and seed breeding on an international level. Your support would help her to reach that goal and help document this important cultural and informational exchange that will benefit our community. See more photos at www.shawnlinehan.com

JOSH VOLK

Josh is vegetable farmer

and the author of the book “Compact Farms: 15 Proven Plans for Market Farms on 5 Acres or Less” from Storey Publishing. He has been a Slow Food member for more than 20 years, and is also involved with the Slow Tools movement which seeks to further Slow Food production through appropriate technology development and sharing. He currently farms

in Portland, Oregon at Cully Neighborhood Farm. You can learn more at www.slowhandfarm.com

FAQ

Where will you find the information that gets collected?

Articles, photographs, video and presentations for the public, all focused on increasing understanding of radicchio production and culinary usage will be published widely in journals and through the participants websites and social media. All information will also be shared at the third annual Sagra di Radicchio event in Seattle, WA in 2020 which we hope to expand into a multi-day conference this coming year.

How can you help spread the word?

Please share this campaign and the resulting photos and write ups widely through social media and other food and farming networks! We love radicchio and all chicories and think they deserve wider appreciation for their ecological, culinary, and cultural contributions.

Why do you keep mixing the terms chicory and radicchio?

Radicchio is a plant in the Chicorium genus, and is probably the best recognized example of that genus in the US and is just one of the cultivated crops in that genus that we’ll be researching. We’re loosely using the term “chicory” to signify cultivated crops of that genus and “radicchio” sneaks in there sometimes for greater general recognition.

Donation Thank Yous

(Shipping is only good for US, outside of the US might be possible but check with us first)

Donate $5 and get your choice of a pdf with our notes from the trip on cultivating chicories, or a pdf of culinary preparations.

Donate $20 and we’ll set you up with the above pdfs as well as stickers and buttons

Donate $50 and you’ll get everything above, and a copy of the beautiful Giáz event poster (check out the website for the event at giàz.com and the poster image on instagram here)

Donate $100 for a signed copy of Compact Farms and Culinary Breeding Network stickers

Donate $250 and we’ll send you an 8×10″ photo by Shawn Linehan, an event poster and we’ll give 3 shout outs on Instagram to let you world know how great you are!

Donate $500 and we’ll get you an 8×10″ photo, 3 instagram shoutouts, and we’ll come to your house to do a multimedia presentation on the trip (in the Portland area – we can travel, but those expenses aren’t included…)

Donate $1000 and you basically get everything, and we’ll do the multimedia presentation at your business (same travel as above)

Really these are all just suggestions – if you want to donate but would like some different combo for a thank you (or nothing at all) just let us know and we might be able to make it happen.

Upcoming Talk

Beautiful day on the farm yesterday and the leeks and fields were looking fine. That single wheel farm cart in the photo is a workhorse on the farm, super easy to load, unload and move large loads in tight spaces with it (if you pay attention to how it’s balanced).

I’m going to be speaking about customizing tools for efficiency (which is the same thing as ergonomics) at the Small Farm Tech Expo in Santa Rosa, California, in early December. Spread the word, I’m looking forward to sharing what I’ve learned and hearing what other folks are doing while I’m down there.

On that note, I’ll be working in the Bay Area (based out of SF/Marin) for the week leading up to that, hoping to visit a few farms I’ve been admiring from afar, and maybe even a few I don’t know about yet.

Farm Hand Carts

The Farm Hand Carts website was hacked last summer and somehow I still haven’t managed to revive it. In the meantime I keep getting requests for the plans for how to build your own that I used to have there and it’s a shame that they’re not still up so I figured I’d post a quick version here until I can get around to restoring all of the information from the old site.

The basic drawing, with dimensions, for the cart pictured above is linked to here. You can change any of the dimensions to match your farm – the two I suggest considering changing are the handle height and the space between the wheels (width of the cart). I set the handle height by measuring the distance to the ground from the tips of my fingers when I’m standing straight up. I want the handle just a few inches below that so I don’t have to bend over much to pick up the handle. For the width of the cart I set the distance between the centers of the wheels to match the distance between the centers of my planting beds. I don’t recommend changing the bed height much, but many people do. For hauling, the cart frame is designed to support a 48″ flat bed, measured from the front of the cart to the back. It should overhang the frame evenly on the front and back of the frame to create good balance and support for the plywood.

I make the carts out of 1 1/4 x .065 square tube and 1″ round tube with a similar wall thickness. The fork legs are 1 1/4 x .25 flat stock. It’s overbuilt, but the added stiffness from being overbuilt makes it easier to move and it’s not excessively heavy.

The cart is designed to be used with standard 26″ mountain bike wheels that are commonly available. Yes, the wheels stick up a little over the frame but I don’t find that they get in my way and the bed of the cart sits just right for easy loading, but still having plenty of clearance. I double and triple stack bins on this cart and have no trouble moving it unless it’s over loaded (more than 300-400 pounds).

The weakest link on the cart is the wheels. They tend to buckle under very heavy load when the cart is going around a turn. Don’t overload the cart and they’ll be fine. If you do overload the cart, make sure the wheels are rolling in a straight line and aren’t getting much side loading (from going over big bumps, or going around turns quickly). If they do break, they’re easier and less expensive to replace than the cart frame itself.

This is a pretty simple welding project for learning on. There’s not a lot of cutting either. Have fun with it and I always love seeing photos of carts in action out there so if you build one please let me know and send me a photo. Thanks!

Winter Workshops

I just updated my workshops page with two conferences and a training program that I’ll be speaking at in California, Oregon and Louisiana. Hit the link to the page, or see below for more details.

The crop planning workshop in December and the CSA workshop at the BD conference in November were very fun for me thanks to great participants and organizers. There are a few more dates in the works and I’ll try to post those as soon as I know if they’re actually happening. Please come say hi if you see me out there on the road.

Upcoming workshops and talks:

- EcoFarm, Pacific Grove, CA, Friday, January 25, 2019 – Compact Farms: 15 Proven Plans for Market Farms on 10 Acres or Less – revisiting farm profiles from the book and what makes them work.

- Oregon Small Farms Conference, Corvallis, OR, Saturday, February 23, 2019 – I’ll be facilitating three workshops on compact farms with a number of experienced growers from around the country: Starting a Compact Farm, Cut Flowers on Compact Farms, and How Compact Farms Evolve.

- Cultivating Small Farm Success, Alexandria, LA, Thursday, March 14, 2019 – Planning for a Successful Market Farm

2018 Numbers

Time for my annual accounting where I try to create a single number that says something meaningful about how the farm did financially. This year, more than the past few, I feel like it’s obvious that numbers in accounting are malleable and really don’t tell the full story without a lot of context.

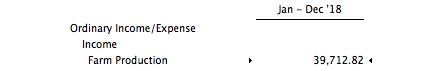

The single number I like to put out each year is the dollars generated by the farm, per hour worked, after (non-labor) expenses. You can look back at last year, and years before that, by going to the blog post on 2017 Numbers. Here are the basic numbers for 2018:

- Gross income – $39,712

- Non-labor expenses – $8,247

- Total hours worked – 1850

The basic math gives a net, pre-labor income of $31,465 for 1850 hours worked, which works out to $17.01 per hour.

That hourly number is before any payroll taxes, so if you’re trying to compare it to an actual hourly wage you need to lop off a chunk. Even so, we’re probably close to the $15/hr range, which feels pretty good, and actually gets us to the target minimum wage for this part of the country. Unfortunately, that still means that folks at the bottom of the pay scale are below that. We’re relatively flat in our pay structure and this year I was able to pay bonuses at the end of the season that made it even flatter.

These are very ball-park numbers even though they look exact. The gross income and hours worked are actually pretty exact, but it gets a little fuzzier when we look at expenses.

I’ve included some non-cash expenses in the expenses – essentially depreciation on equipment like the walk behind tractor and implements, and other structures. I’m pretty consistent about this in my own calculations, and it helps to even out the picture in years that have drastically different investment levels in tools and infrastructure. Beware that if you’re comparing to your numbers our methods might not match.

This year looks better than the past few and here are my best guesses on the reasons why. The primary reason is luck. A lot of things lined up for us this year: the weather was pretty good, we had great folks working with us who were available at the right times, and we were able to sell most of what we produced with very little waste. Certainly we set ourselves up to take advantage of those kinds of conditions, but even with experience (and partly because of experience) I know that there was an element of luck that certainly helped and we won’t have that every year.

Another factor that’s making the 2018 number look better than previous years is that we went really lean on expenses this year – something that probably isn’t sustainable. We weren’t sure if it was going to be our last year on the property (turns out it looks like we’ll get another year, maybe more) so we relied heavily on the tools, seeds and supplies we had on hand and didn’t have to spend much on non-labor expenses. I actually invested in a few tools for 2019 right at the end of the year but I didn’t put those expenses into the above numbers. If I had they would drive the non-labor expenses up by almost $2000. That changes the hourly number to $15.93. With luck, those investments in tools will improve our efficiency enough to pay back at least a portion of that $2000, and they should probably also be depreciated as they will mostly all last numerous years.

A few final pieces of context here. You can go to cullyneighborhoodfarm.com to get a better sense of the scale and practices of the farm. We’re growing on a lot that’s just under an acre, with just over ½ an acre in production. We’re not pushing our production particularly hard relative to many compact farms. Nearly all of income comes from CSA shares, but do make a little on top of that from some mid-season farmers market sales, by selling extras straight from the farm.

I’d love to see this same basic analysis from other farms and I welcome ideas for improvements to my method.

Corn and Beans for Sale!

I’ve made a new page for crop sales here – but I’m also posting all of the information here, just below. If you’re interested in getting a little corn read on and order soon, quantities available are quite small.

UPDATE 12/13 – Less than 24 hours after posting this I’m sold out of the popcorn and Pigna beans but we still have a small quantity of the Tolosaka, Piatella and Sorana beans available, and plenty of Otto File corn. If you already ordered I’ll be sending order confirmations this afternoon. Thanks for all the orders and keep ’em coming!

The 2018 crop of Dakota Black popcorn and a small offering of dry beans is up for sale for a limited window, and I also have some remaining Otto File polenta corn from the 2017 season. These were all grown at Cully Neighborhood Farm in NE Portland.

Here’s the price list and descriptions of the offerings, ordering info is at the bottom of the page:

Dakota Black Popcorn

$6 a bag (2 cups of whole kernels, a bit more than ¾ pound) – Most of this went to our CSA at Cully Neighborhood Farm this year but we had a number of odd shaped ears with perfectly good kernels on them so I shelled those and I’m offering them here. I just popped a batch yesterday and it continues to be excellent with a high percentage of popped kernels that come out medium sized, bright white and with great fresh popcorn flavor, not at all like the big stale stuff you get in most bulk bins.

Otto File Polenta Corn

$4 a bag (2 cups of whole kernels, a bit more than ¾ pound) – A few years ago I was in Italy and visited a wonderful little biodyanamic market farm in Lucca. The farmer gave me an ear of his golden polenta corn (otto file, meaning eight rows in english – because there are eight rows of kernels on the slender cobs). I ended up planting it in my garden and it made amazing polenta – tons of corn flavor, beautiful golden color, slightly sweet – so I grew more. I use a relatively simple Corona hand mill to grind mine as I need it, but there are many other options out there. It can also be cooked whole.

Dry Beans

$6 a bag (2 cups of dry beans) these are all specialty varieties of dry beans and I only have very limited quantities. If you’ve only ever had canned dry beans, or beans from the bulk section, these are a completely different experience. They are cook easily and evenly and have an extra layer of flavor. In general these all have delicate skins and cook well by soaking overnight, bringing to a boil and the gently simmering for 45 minutes to an hour. Add salt and other seasoning to taste, generally about 1-2 teaspoons of salt per bag. Be sure to save the cooking liquid which is delicious. Variety descriptions follow…

Tolosaka

This is my name for the tolosa black bean, which I’ve been growing since 2007. This is a beautiful, large, deeply black bean that is from the Basque region of Spain. Look it up, apparently it’s famous. I just know it’s delicious and one of my favorites.

Pigna

Another one I’ve been growing since 2007. A large round white bean originally from Spain but also grown in Italy. It’s a Slow Food Ark variety and you might try to find it from the Italian growers if you really like it and support their efforts to keep it growing in its traditional areas.

Sorana

A great little white bean, very tender and tasty. Lane Selman and I brought this back from Italy by request for Uprising Seeds in 2014 and they shared seeds from their first grow out with me the following year. I’ve been growing it for the past two seasons and it’s quickly becoming a favorite for its great flavor. It’s a Slow Food Ark variety and you might try to find it from the Italian growers if you really like it and support their efforts to keep it growing in it’s traditional areas.

Piattella

Quantities are extra limited for this flat, white bean. I got this one from a grower in Italy who also uses corn for trellising. It’s a Slow Food Ark variety and you might try to find it from the Italian growers if you really like it and support their efforts to keep it growing in it’s traditional areas.

Ordering

All orders are packed here in the St. Johns neighborhood of Portland, OR and are available for pick up on my porch. To order Send me an email (by clicking on “send me an email”) with your order including the items you’d like and the quantities. I’ll send you the details for the pick up location, how to pay, and when your order will be ready (usually in a day or two). I’ll be packing orders through December 21, 2018 before taking a break for the holidays, or until I sell out.

Upcoming Workshops

It’s been a busy conference season for me, five in less than two months and two more coming up before the first week of March.

The Oregon Small Farms Conference is this Saturday. It’s one of the best conferences I go to anywhere in the country. I think part of that is that it’s really focused on Oregon and small farms. It’s only one day, but the day is full of quality talks that relate directly to production issues. I’ll be co-presenting in a session on Vegetable Pack Shed Layout and Ergonomics with Nick Andrews, Heidi Noordijk, and Andrea Kramer. My piece will largely be around the three pieces of equipment that I prototyped for their new pack shed, all written up over at joshvolk.com: an adjustable height spray table, a tote washer, and a packing table. The conference is sold out, but if you’re already signed up, come see our talk and we’re planning on having the prototypes there, along with the trailer that’s been converted into a cooler that Nick and Heidi made.

Not sold out yet (as far as I know), is a day long workshop I’m doing for SnoValley Tilth up in Carnation, Washington. The workshop is titled “Efficiency and Ergonomics on the Farm: Setting up tools, systems, and work spaces for speed, safety and happiness” and I think that pretty much covers it. Thanks to a generous donor the price is incredibly low so if you’re in the area it should definitely be worth checking out. I’m going to be mixing it up with both slides and hands on demos.

I’m trying to keep my workshops page up to date with upcoming talks as they get added. I also try to repost new additions here on the blog and on my Facebook page so you can keep track of where to see me by checking any of those spots.

2017 Numbers

Every year I take a look back at the previous year to see how we did and what I want to do better in the following year. Part of the analysis I’ve been doing is to add up the gross income and then subtract out the non-labor expenses. This gives me a net for all of the hours of work that went into the farm. Then I add up all of the hours worked and divide. This gives me a net per labor hour.

You can look back at my write up from last year to get a more detailed explanation of how I’ve been doing this over the years (and links to more write ups from years past). Instead of making this a long post I’ll just refer you back there for the explanation.

In 2017 I worked with Matt Gordon at Cully Neighborhood Farm again. We grew for 60-ish CSA members, and sold a little excess produce through the Cully Neighborhood Farmers Market. We grossed about $36,500 on about 1/2 acre so roughly $73,000 per acre, down very slightly from 2016. The non-labor expenses was about $10,000. Adding in the depreciated BCS expense brings that number up to about $10,940, a little under 30% of gross so we were able to keep the expenses down this year, despite making some infrastructure improvements that really improved ergonomics on the farm. The total hours worked on the farm, including marketing and administration, field work and everything else, was about 1910 hours, so we cut that back a little as well. That gives a (pre-tax) dollar per hour number of around $13.40 across the farm, up almost 4% from last year, which was better than inflation so I think we’re making progress.

For those with an eagle eye, you’ll probably notice that we’re right around Oregon’s minimum wage when you adjust for a “loaded” hourly wage (one that includes payroll taxes). Still, the bottom line is that for now I’m happy with that number for 2017 and we’ll take that information, along with the rest of the numbers we’ve collected and see if we can continue to improve in 2018.